Taliesin West

By Margo Stipe

Taliesin West is one of the world’s great architectural treasures. Situated on more than 500 acres, it is a National Historic Landmark and has been nominated for inclusion on the UNESCO World Heritage List.

Wright described Taliesin West as “a look over the rim of the world.” Here the elemental and ancient met the present and the boundary between landscape and architecture blurred. The complex includes interior spaces (the Cabaret Theater, Music Pavilion, Kiva, Wright’s private office, the dramatic Garden Room, private living quarters, and the Drafting Studio), linked by terraces, gardens and walkways overlooking the rugged desert and distant metropolitan Phoenix area. From the beginning, this set of buildings nestled in the foothills of the McDowell Mountains amazed architectural critics with its beauty and unusual form.

“Taliesin West is one of the supreme triumphs of site planning in American architectural history,” wrote architectural critic Martin Filler. “It is a structure …set with immense care and subtlety in a scene of almost overpowering beauty.” With an almost seamless integration of indoor and outdoor spaces, Taliesin West was a bold new architectural concept for desert living, literally built of the desert. Of this architectural experiment Wright said. “Our new desert camp belonged to the Arizona desert as though it had stood there during creation.”

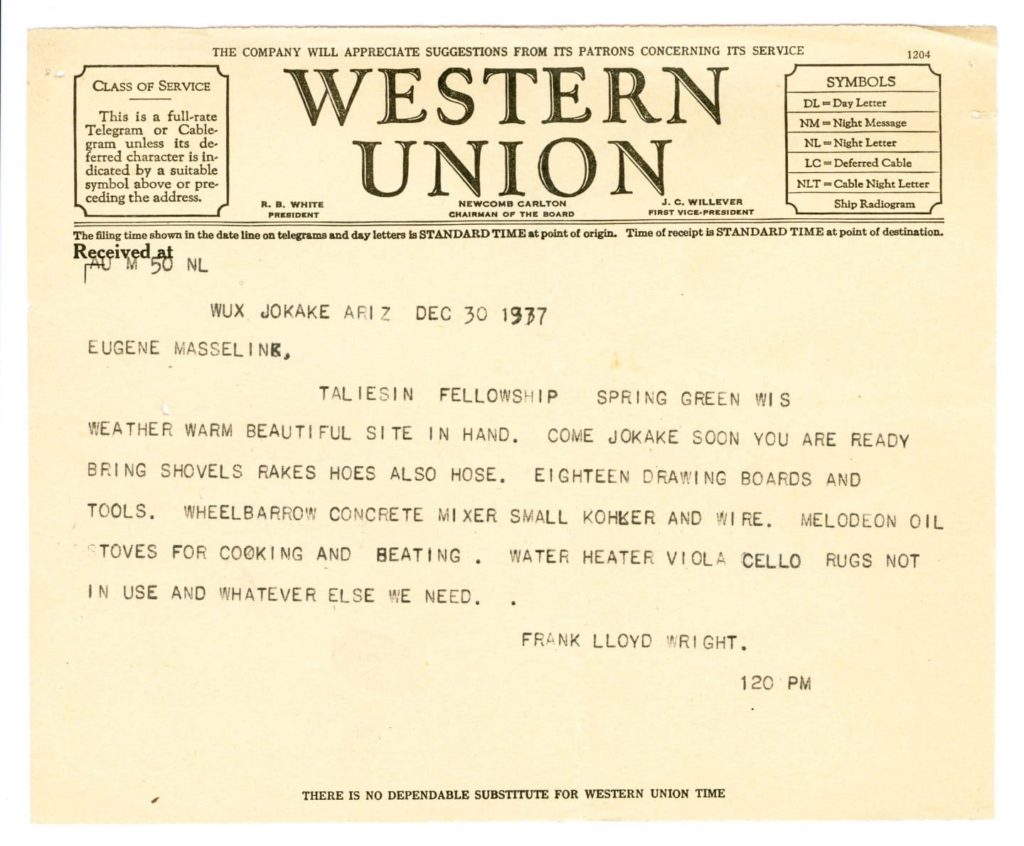

At 70, an age when many people have retired from their working life, Frank Lloyd Wright, accompanied by his wife and about 30 young men and women who were apprentices in architecture, arrived at a vast, unpopulated sweep of land on the Arizona desert at the foot of the McDowell Mountains with sleeping bags and rudimentary camping equipment. With no fanfare, but much youthful enthusiasm, they began clearing the ground, building temporary shelters, and preparing the site for what would become a very unconventional winter home.

This new building was to be a southwestern headquarters—living quarters, studio, home and workshop–for the Taliesin Fellowship. Established in 1932, the Taliesin Fellowship was an apprenticeship training experiment in architectural education. It was barely five years old when the Wrights decided that living in Wisconsin during the brutal winter months was cramping the style of the group who were eager to be busy and actively learning architecture by actually constructing buildings.

The seeds of Taliesin West were planted during an earlier sojourn to the southwest. In 1927 Wright had first come to consult on the design of the Arizona Biltmore Hotel, a new resort for Phoenix. During this visit, Wright met Dr. Alexander Chandler, of the town that took his name, some miles south of Phoenix. Chandler, a veterinarian from the Midwest, who discovered that cotton grown in the region was ideal for the manufacture of rubber tires. He went cotton growing, and quickly built up a fortune which he turned into the tourist business. He had long wanted to build a new hotel resort and believed Frank Lloyd Wright was the perfect architect to design it. The resort, San Marcos-in-the-Desert, was to have been located on the southern slopes of South Mountain.

While working on the hotel, Wright elected to move out onto the desert and build a temporary camp, which he called “Ocatillo.” This camp was composed of a group of box-board cabins roofed in canvas connected by a low box-board wall. Necessary openings were created by canvas-covered wood frames, the flaps hinged with rubber belting. Wright wrote of it, “when all these white canvas wings, like sails, are spread, the buildings will look something like ships coming down the mesa, rigged like ships balanced in the breeze…”

Ten years later, Wright returned to Arizona intent on establishing a settled winter camp to which the group would return annually. Once a suitable site was found, plans for Taliesin West blossomed. Remembering the wonderful light from the canvas used at Ocatillo, Taliesin West was also planned as a canvas-topped structure. But in place of the perishable wood used in the earlier camp, the abundance of native stone, richly varied in color and shapes made possible a supporting structure of concrete and stone masonry.

The site and its relation to the mountain range to the north dictated the orientation of the plan. The axis, tilted off a direct north-south orientation, is derived from the extended view, from the west, looking east to a group of isolated mountains: Black Mountain and Granite Reef Mountain. By tilting the plan off the direct compass points the sun and shade had their play throughout all the rooms and vistas throughout the year.

Taliesin West was designed as one opus set on concrete terraces, surrounded by massive low masonry walls. Wright told the apprentices that the desert was like a revelation to him: “I was struck by the beauty of the desert, by the dry, clear sun-drenched air, by the stark geometry of the mountains, the entire region was an inspiration in strong contrast to the lush, pastoral landscape of my native Wisconsin. And out of that experience, a revelation is what I guess you might call it, came the design for these buildings. The design sprang out of itself, with no precedent and nothing following it.”

The first challenge to be met was how to build with the native stone that could not be tailored or cut, like limestone or sandstone; how to build a strong masonry wall with minimum expense and minimum use of skilled labor. Since the available stones had a smooth, flat face on one side, the smooth surface was placed into a temporary wooden form, the curved boulder-like part of the stone remaining in the center of the wall like “fill.” Concrete was then poured around the stone, moving up the surface of the wall inside the form with more stones, and more rubble-fill as required. It was from the variety of the colors and shapes that the wall took its character, truly mosaic-like. It was the artistic and carefully chosen placement of the stones that determined the resultant beauty.

“The desert abhors the straight, hard line,” Wright stated, citing the cactus to illustrate the natural “dotted” line. To introduce the dotted line into the forms of Taliesin West, he used many details, mostly executed in wood. Along the edges of fascia boards, for example, were placed 2″x 2″ dentils–cubes of redwood spaced 2″ apart, running in a steady line. As the sun moves across the sky, the shadows cast by these dentils form as much a part of the architecture as the boards and cubes themselves.

Shadow is an important element in the overall design. The great redwood trusses that held the canvas overhead are examples of a carefully planned geometry which creates shadows along the structural members themselves, as well as casting interesting patterns on the stone walls and concrete terraces above which they rise. There is little rectilinear planning in the building-slopes and prominent angles throughout abstractly echo the angles and slopes of the surrounding mountains.

From the beginning the main rooms, the office, the drafting room, and the Garden Room, were to be roofed with canvas, the diaphanous textile setting up a dramatic contrast with the massive, almost fortress-like, stone masonry. Wright continually revised the roof. No two photographs, taken a year apart of the same room, show the roof the same way. It was as though on a great stone masonry foundation, as a steadfast rhythm, the architect kept modifying the melody, this delicate light-filled overhead.

In those early years, living in this tent-like structure, everyone learned that the desert could be inordinately cruel. The sun could parch everything under its rays; great wind storms could sweep across the land like small fast-moving tornadoes, throwing dust and gravel high in a column that came upon the buildings and tore canvas from their wooden frames, wreaking havoc within. And during the monsoon season, the desert floods could be hazardous. The soil all about is non-absorbent because of its composition of sand, rocks and gravel. The rain water, coming off the mountain slopes behind, came in torrents–like a moving tidal wave, turning the dry washes into turbulent rivers, pouring across the territory and everything in its path.

But the romance and the beauty far outweighed any of the seasonal hardships. It was Wright’s original intention that Taliesin West be truly a tent-like structure, the canvas roofs and flaps put in place during the winter and taken down and stored during the summer. But this meant during particularly inclement weather, the spaces were totally enclosed by the canvas. Early on Olgivanna asked about bringing in glass, but Wright was adamant about the experiment with this canvas. One season, however, when the skies were grey for weeks on end, the desert was in its “wet” cycle, and rain poured down, she tried again. Through clever storytelling about a dream of glass, Wright was finally persuaded to have some glass installed. Glass came in as skylights, set between trusses, mitered down onto great beam ledges, along stone walls and in garden courts. The desert in all its changing states–bright with sun, drenched in rain or clouded with dust, quiet under the star-filled night sky–was a constant spectacle that could now be seen from within the buildings during colder winter weather.

The buildings changed constantly, as Wright saw ways to improve them as the times and conditions of life changed. During the last two winters of his life, Wright himself began to introduce a more permanent, less camp-like quality throughout the site. To this day with all the new and modern “improvements” that have come on the scene since it was first built as a primitive campsite, Taliesin West still manifests the original sense of powerful, rugged drama. Antiquity and modernity go hand in hand at Taliesin West and Time seems to have come to a halt. It has a magical power that never ceases to grip those who live here and to amaze many of those who experience it for the first time.