Petroglyphs at Taliesin West

By Aaron Wright, Ph.D.

Discovering Frank Lloyd Wright’s work during a high school field trip to Fallingwater, Preservation Archaeologist Aaron Wright, Ph.D., felt drawn to Wright’s understanding of natural landscapes. Now, 25 years later, he is revisiting the legendary architect’s work to study the petroglyphs at Taliesin West.

This project has been funded in part by a grant from the Bonderman Southwest Intervention Fund of the National Trust for Historic Preservation.

In 2016, Stuart Graff, president & CEO of the Frank Lloyd Wright Foundation, reached out to me with an interesting proposition for a collaborative endeavor. No, it had nothing to do with the common last name, but everything to do with an interest shared between myself, Frank Lloyd Wright, and the Foundation’s staff — petroglyphs.

Technically speaking, petroglyphs are human-made figurative impressions in stone. The term, however, is used most often by anthropologists and archaeologists when referring to the pictorial works of societies who share (or shared) knowledge through oral traditions rather than formal writing. Petroglyphs are generally studied within a broader subject of stone-oriented visual culture sometimes called “rock art,” which includes pictographs (paintings on stone) and geoglyphs (designs on the earth surface created by the selective placement or removal of stones).

Unlike hieroglyphs, which are ancient inscriptions and paintings that can translated, petroglyphs (as well as pictographs and geoglyphs) lack the structure or grammar of written language. This leads the unfortunate reality that there is no sure way to interpret them. Nevertheless, the inscribed figures and designs surely held meaning for the those who made them, and even today people from many different walks of life continue find meaning in them. That we cannot “read” petroglpyphs does not nullify their timeless value and importance.

For anyone who has toured Taliesin West, the petroglyphs positioned throughout the property are hard to miss. Albeit easy to see, the petroglyphs’ broader cultural and historical significance is not so self-evident, and that is where my path crosses that of the Foundation. I’m a Preservation Archaeologist at Archaeology Southwest, a nonprofit organization in Tucson dedicated to exploring and protecting the places of our past. My background is in the archaeology of southern Arizona, with a particular interest in how people crafted and used petroglyphs, and how these signs and their intentional placement within the landscape can teach us about the ancient communities responsible for them, including their social values, aesthetics, and religious practices.

Petroglyphs are created by any means of “cutting” into a rock’s surface—scratching, etching, carving, pecking, chiseling, grinding, or abrading—usually with the intent to penetrate a dark exterior (a rock coating called “desert varnish” that is created by microorganisms) to expose a lighter-colored heartrock. It is often the resultant bichromatic color contrast, more so than alteration of the rock’s surface texture, that catches one’s eye and draws focus to the image. The vast majority of petroglyphs in North America can be attributed to Native Americans over the last 10,000 years. The desert regions of the American Southwest are renowned for many different styles of petroglyphs, bold and intricate assemblages of geometric, animalistic, and human-like figures adorning boulders, cliffs, and alcoves.

Frank Lloyd Wright was fascinated by the petroglyphs he saw in southern Arizona. It is not a coincidence that he located his winter home adjacent to a cluster of petroglyphs at the foot of the McDowell Mountains outside of Scottsdale.

Mystified by their historicity and continued spiritual significance to Southwest Native American communities around Taliesin West (specifically the O’odham, Piipaash, Hopi, Yavapai, and Apache), Wright incorporated the petroglyphs into his architectural designs.

He went so far as to hoist several colossal petroglyph-adorned boulders from the hillside and delicately situating them at visually prominent and inviting points around the buildings. One particular sign, a set of interlocking rectilinear scrolls, was the inspiration for Taliesin West’s “clasped hands” or “whirling arrow” logo.

In May of 2017, and at the invitation of the Foundation, I embarked on a project to better understand the petroglyphs at Taliesin West, as well as Frank Lloyd Wright’s connection to them, the inspiration he drew from them, and how he recontextualized them into an organic-albeit-built environment in the Sonoran Desert. This is one of the untold stories of Taliesin West—a chapter in Wright’s architectural narrative that has yet to be fully explored and thus lingers as an under-appreciated strand of his enduring legacy.

Our long-term goal is to integrate this aspect of Wright’s vision and experimentation into the visitor experience at Taliesin West. It is an opportunity for visitors to move beyond appreciating Wright’s architectural work and learn about the architect, as a person, what inspired him, and his understanding of archaeology and relationship with tangible vestiges of the past.

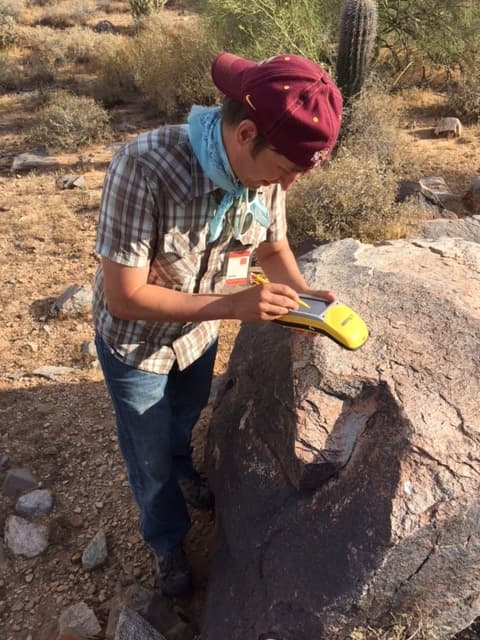

Such an aspirational project, however, starts at a very foundational level. The first stage of this project entailed locating all of the petroglyphs on the Taliesin West campus, evaluating their physical condition, and considering their natural and archaeological setting. This entailed ascertaining high-precision geolocational data (i.e., GPS) for each petroglyph boulder. While doing this, I was joined by Paul Vanderveen, a local photographer with a keen eye for petroglyphs.

This initial phase of the project also offered the opportunity to explore the utility of photogrammetry for documenting the petroglyphs at Taliesin West. Photogrammetry is the science of making measurements from photographs, whose end product is typically a to-scale map or other multidimensional representation of physical space.

While photographs are tried-and-true, one of our goals is to create 3D models of the petroglyph boulders at Taliesin West. To do so, I took several hundred photographs of each petroglyph boulder, all from different angles and depths. I shared these with my colleague Doug Gann, Preservation Archaeologist and Digital Media Specialist at Archaeology Southwest, who created this 3D model of one of the boulders.

Considering that this model represents just one percent of the available data (in order to save digital storage space), it looks like photogrammetry opens new doors for sharing the petroglyphs at Taliesin West with a broader audience and in novel ways. Our work has just begun.